“Why don’t you go somewhere a little more…different?” asked my friend from Birthright when I told him I wanted to spend a year teaching English in Israel. He was remembering the way we had experienced Israel on Bus RT-38-485, speaking English with everyone we met, browsing the same souvenirs in the shuk we’d seen at Venice Beach, and ordering pancakes at a Tel Aviv café. But I wasn’t seeking the thrill of living abroad. I was interested in volunteering in Israel because I’d learned from my family that doing so could help you discover yourself. My grandparents met there while my grandfather was helping to resettle orphans after World War II, and my dad still dreams of his year on Kibbutz Kinneret, where he learned Hebrew and became an adult. I’d grown up thinking that they did this, in part, to ensure that future generations could do the same if we wanted—volunteering in Israel always seemed like a break-in-case-of-emergency option. Now, I was ready to shatter the glass. I had spent my twenties feeling like I was constantly making mistakes, from the nitty-gritty work stuff to my choices of cities, apartments, and boyfriends. I thought teaching might suit me better than my previous career path, but I didn’t have a lot of financial wiggle room to make another miscalculation. The fact that I could try it out through a subsidized program like Masa Israel Teaching Fellows felt like a gift.

Regardless, I took what my friend said into account when I chose to do the program in Haifa, a city with a reputation for diversity. I was also thinking about it when our group leader met with each of us and asked what type of school we’d like to work in. She explained that the school system in Israel is segregated by religion and language. Students here attend Jewish religious or secular schools conducted in Hebrew or Arab schools conducted in Arabic. Families can technically send their children to any of the above, but most people stick to schools that represent their own identities. While I was familiar with Jewish Israeli culture from my family and knew I’d absorb it simply by being in Israel, I knew nothing about Arab Israeli culture. This was a unique opportunity to learn something new that would be hard to replicate on my own. Plus, teaching was teaching, and my workplace wouldn’t affect my ability to wander around taking pictures or scribbling about the meaning of my life in a coffee shop. So I said I wanted to teach middle school, and that an Arab school sounded cool.

I started teaching at Ras Ali and Khawaled, a K-8 school serving two villages near Haifa. The families who live in Ras Ali, where the school is located, have been farming in the valley below the tree-lined slopes surrounding its river since before 1948, and people from nearby Khawaled are Bedouin. It was immediately clear that I had succeeded in finding someplace different. Everyone was speaking Arabic, and the only two words I recognized were sababa and yalla. My students asked me to name Arabic-speaking countries and I messed up by guessing Iran, which caused them to erupt with indignant laughter. While most of my students tackled me with high-fives and hugs in the hallway, I understood that teaching when I didn’t have fluency in the language or the culture meant I’d have to work hard to earn their respect in the classroom. Otherwise, they’d stop listening, walk out of the room, or worse, stay in it and fight. This should have been discouraging—I’ve cried at work in the states over less.

But for some reason, it just…wasn’t. Being a completely blank slate when it came to this culture and job meant that I had no preconceived notions about the situation or myself. It didn’t matter if I didn’t know what knaffeh* was or how to quiet students down because I never thought of myself as the kind of person who should. Pretty quickly, I found that being a newbie suited me. Having chosen a different environment freed me to ask questions, mess up, and be wrong. And I did, all the time. I spent my first few months on the program watching YouTube videos about the basic fundamentals of Islam, making my host teacher, Kholood, coach me on how to clarify things for the students in Arabic, and asking people to repeat their names approximately 500 times.

Being willing to be wrong is only half as important, though, as being surrounded by people who tell you it’s okay to be. The staff and students at my school have been the most welcoming and good-natured teachers. Our principal, Mysoon, hosted me at her home in Kabiyya for a whole weekend. I savored my time there, picking oranges from her tree as her husband grilled and her daughters brought salads to the table. I learned the Arabic alphabet from her children, taking notes on how to pronounce the new sounds. Kholood and I spend our morning commute talking about the art of learning a language, what’s going on with our students, and how to be accepting of all kinds of people. She always guides me so gently toward the right thing, never shaming me for making mistakes, harshly correcting me, or making me feel like an outsider. Each week, she patiently explains everything that happens in the school in English so I don’t feel out of the loop. On my first day, I made friends with our English- speaking custodian, Abu Noor, when he brought me Arabic coffee and taught me how to say sabakh alkheir (“good morning” in Arabic). Since then, he has been a reliable source of memes and jokes, Arabic tutorials, and labneh, which we call Home Cheese because it’s made in the village from local sheep’s milk, and is therefore much more desirable than the store-bought version. When my dad came to visit, he introduced himself to Abu Noor as “Abu Sarah,” a play on the Arabic tradition of calling a man “Abu,” for father, paired with the name of his oldest son. Now they both call me yabinti, which means “my daughter.” Last week, my seventh-grade students invited me to spend the afternoon with them in Khawaled. Every time we turned a corner, I saw one of my students on a bike or waving at me out the window of a house. We walked to the shop to get ice cream bars and then another teacher, also named Kholood, invited us in to play cards and have dinner. I felt like a kid again and wished I had grown up in a village like this. When I told her about this visit, my roommate observed that a village is a place where the boundaries of what’s yours seem to extend beyond the walls of your home.

I know that the support I feel from my school is why I’ve fallen in love with teaching. I’m proud of how much better I’ve become at engaging my students, especially since, as Kholood recently reminded me, kids don’t fake it. Watching them get competitive when we play games or remember a word and use it to communicate with me in English gives me the kind of career satisfaction I’d been searching for in the states. Around the 5-month mark, I realized that I feel more like myself in this place I never imagined I’d be than I ever felt at home. Now I know that I wouldn’t have figured this out just by putting on a pair of shuk-bought sandals and journaling in a coffee shop. I’m lucky that I had the opportunity to come to Israel in search of myself. But I am even more fortunate that I came here and discovered something beyond myself.

When our group leader asked me to speak to MITF participants from other cities about what it’s like to work in an Arab school, I realized it was true that I wouldn’t have gotten such a thorough understanding of the different cultures in Israel if I’d been placed at a Jewish school. Many of the other MITF fellows I spoke to had asked questions that showed me they were still unfamiliar with the specifics of Arab culture or were even a little intimidated by it, perhaps because of things they’d heard from their families or the media. A lot of Jewish Israelis I met held more overt biases. One said that she thought it was cool that I was working at Ras Ali, but the only question she asked about it was whether I felt scared there. I was sad that they asked these types of questions, but I also understood why they did. Keeping people separate ensures they will never have a chance to relate.

My feminist training in the states taught me that the personal is political, and the concept applies here, too. In general, if you have a friend who’s different than you, you’re more likely to care about the well-being of that friend’s people. Israel programs always inevitably include time to reflect on what it means that Israel is a Jewish state. During this time, I’ve thought a lot about how more than one group of people have a historic connection to this land. My Jewish ancestors envisioned Israel as a place where their children (and their children’s children) could find themselves, thrive, and carry on our religious and cultural traditions. But if it was my predecessors who made it possible for me to come to Israel, it has been representatives from another group of people, with an equally rich history and beautiful culture, who have made my specific experience here so meaningful.

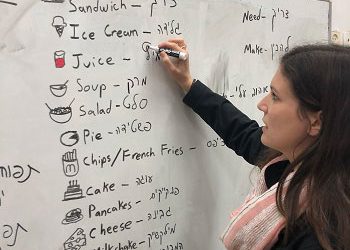

Since I started working at Ras Ali and Khawaled, I have been reading more about the history of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and the inequalities that plague Israeli society, language education being one of them. Everyone in Israel learns English beginning in third-grade, but Arab students learn and gain fluency in Hebrew while only 10 percent of Jewish Israelis become fluent in Arabic. This strikes me as unhelpful in the effort to create mutual understanding. If education perpetuates misunderstanding here, though, it also offers us an opportunity to change it. You can’t really understand someone if you don’t get to know them, and getting to know them is easier if you speak their language. I’ve come to believe that everyone in Israel should be striving to learn English, Hebrew, and Arabic, myself included. I am so convinced that language education can be a strong starting point for making friends and signaling open-mindedness that I’ve started researching how I can stay in Israel after the program to work in this field. I’d like to continue teaching English to both Arabic and Hebrew- speaking students, ideally in a diverse school. But I don’t want to get too ahead of myself, because, for the first time, I’m not wishing my life away. For now, I’m just eating Home Cheese and willing each day in Ras Ali to feel longer than the last.

*Knaffeh is the most delicious food that exists, and if you haven’t you should try it immediately. If this isn’t an option for you at the moment, at least Google it so you’ll know you need to eat it when you encounter it in the wild.

Sarah Davidson is a 2020 Masa Israel Teaching Fellow with Israel Experience in Haifa, teaching at Ras Ali school.